Trump and Transactions

Along with some thoughts on the U.S. constitution and the Latter-day Saint tradition

For the foreseeable future, it is very likely that this substack will consist mainly of my thoughts on the dangerous mountebank in the Oval Office and the various rotten things he is doing to my country and the world. You have been warned. Today, I have some thoughts on Trump taken from contract law theory. However, to leaven the Nate’s-contempt-for-Trump-filtered-through-strange-law-prof-lens content, I also have thoughts on Mormonism and the United States constitution, which may or may not be timely.

Trump and Transactions

Trump’s approach to politics and diplomacy has been described as transactional. He thinks in terms of deals, and defines success less in terms of long-term strategy than snookering the the person in front of him into the best deal possible. This, in the eyes of his defenders and acolytes, is the Trumpian “Art of the Deal,” the application of a hard-headed business sense to politics.

Except it isn’t.

Trump’s transactional approach consists of a willingness to torch long-term relationships in the service of short-term advantage. Hence his indifference to undermining trust in American commitment to NATO or treating our oldest allies as adversaries in a trade war (or worse!).

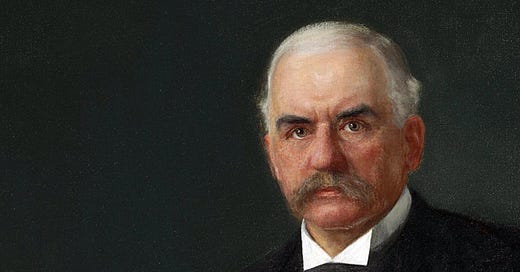

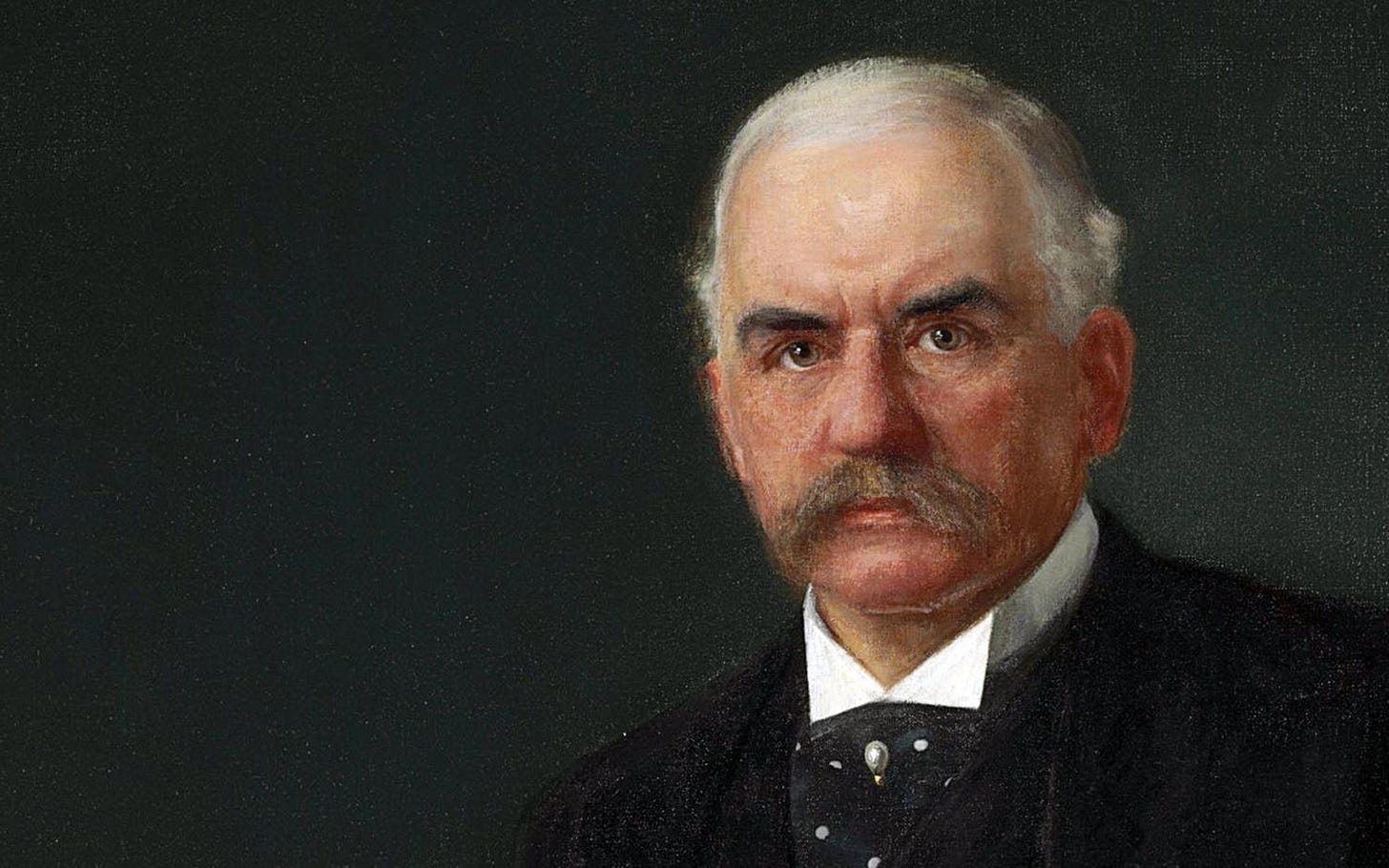

Here’s the thing: This isn’t how successful deal makers behave. As J.P. Morgan — who unlike Trump, actually was a titan of capitalism — put it, “A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom. I think that is the fundamental basis of business.” Being a reliable, trustworthy person is actually an enormously important part of being successful in business. If every interaction is treated as a self-contained transaction with a zero-sum winner or loser, it is impossible to create long term relationships and commercial success is impossible without such relationships. Those relationships, in turn, are founded on trustworthiness. The economist David Rose, in his excellent book The Moral Foundations of Economic Behavior, put the point in terms of “golden opportunities.” These are chances to behave opportunistically that cannot be detected. Because such “golden opportunities” are ubiquitous, they create a crippling drag on economic activity unless one has some assurance that counterparties will behave in a reliable and minimally and predictably ethical manner. For markets to functions, people not only must be perceived as being honest and reliable, they must in fact be honest and reliable. Those who consistently behave opportunistically will be shunned within a market where there are repeats players. If there are too many such actors, the market will simply fall apart.

Donald Trump’s own career illustrates this dynamic. He has not been a tremendously successful businessman. He inherited substantial real estate holdings. He has managed, borrowed against, and built a larger set of real estate holdings and — crucially for Trump’s sense of himself — has moved from cheap apartment buildings in the outer Burroughs to prestige property in Manhattan. But at the end of the day, the growth hasn’t been spectacular. If he’d put his inheritance in an S&P 500 index fund and done nothing, he would probably be a richer man today. Along the way, however, Trump has managed to make himself a business pariah in much of the American market. He routinely ignored contracts, stiffed suppliers and workers and then dared them to sue, and burned banks that lent him money. By the time he turned to politics, no major American bank would work with him, and he was dependent on European institutions for funding. There is a reason he was on television. Real capitalist masters of the universe don’t waste their time as gameshow hosts.

Trump’s problem is that if you spend a lifetime taking a transactional approach to business transactions, fewer and fewer people want to transact with you. Trump is now applying this approach to America’s diplomatic relations. There is essentially no concern with the long-term credibility of American promises or intentions. Instead, the focus is purely on the transaction in front of him. This isn’t the application of hard-headed business tactics to government. Rather, Trump’s actions are those of an at best mediocre executive who doesn’t really appreciate what makes commerce function. It’s bad business. As state craft, I think that it has already harmed American power in ways that will take decades to repair even if we started tomorrow, which (of course) we can’t. Trump is pissing away decades of the accumulated diplomatic and political capital of the United States in pursuit of a few press-release victories for a relatively small share of the American electorate who aren’t ultimately going to get any real benefits from the victories. I am watching the trust and goodwill of Atlanticist friends in the UK and pro-American Canadian friends ebb away in real time. It’s heartbreaking. Worse, it risks remaking America in the image of the Trump Empire, a glitzy but ultimately shoddy conglomeration that exists to flatter Trump’s ego but generates very little real value.

The Constitution and Religious Freedom in the Latter-day Saint Tradition

As I have mentioned before, last year I published two volumes collecting my writings on law and Mormonism. The first volume looks at issues in Latter-day Saint legal history, and the second volume looks at legal ideas in Latter-day Saint theology and scripture. Some of these papers have been previously published, and you can get a sense of their content by, for example, taking a look at this article on the role of law in the Church’s international expansion in the 20th century and its effect on Latter-day Saint teachings about politics and the state. Alternatively, you can check out this paper on legal interpretation in the Book of Mormon.

In addition to the papers collected in those two volumes, for the last few years I have been working on and off on a third book about law and Mormonism, one that tries to offer a more comprehensive view. I have finally finished it, and the book, entitled Living Oracles: Law and the Latter-day Saint Tradition, should be published by Oxford University Press in the next year or two. To give a sense of what it will be like, I have posted one of the chapters online. Here is a summary:

In the wake of the violent expulsion of the Latter-day Saints from Jackson County Missouri in 1833, the United States Constitution and its promise of religious freedom appears for the first time in Mormon scripture as a product of divine inspiration. The idea that the U.S. constitution is divinely inspired has been used in various ways by Latter-day Saints, as well as at times posing theological and practical problems. This chapter, which will be included in a forthcoming book on the Latter-day Saint legal tradition, traces the history of this idea, showing the various forms it has taken as well as its relative decline within contemporary Mormonism. The arc of the U.S. constitution as an element of Mormon religious discourse and practice in many ways encapsulates the broader themes of the Latter-day Saint legal tradition. The appearance of the constitution in Joseph Smith’s revelations after the creation of a set of texts resolutely ignoring contemporary political or legal structures illustrates the way that modernity and pre-modernity co-exist within Latter-day Saint thought. The very intrusion of a secular legal document into the Latter-day Saint scriptural canon testifies to the way that law has been a driver of religious and theological change. At the same time, American constitutional practice has often failed to live up to the religious expectations of Latter-day Saints. Law thus becomes both a way in which Latter-day Saints have conceptualized their membership in a larger non-Mormon community, as well as a site of religious anxieties.

If you are interested, you can download the entire chapter here.

Until next time,

Nate Oman

A thoughtful piece. Thank you.